Luke's Working Notes

Powered by 🌱Roam GardenHaack's Crossword Puzzle Analogy

Susan Haack's crossword puzzle analogy can be used to analyze the propositional elements (assumptions & beliefs) of a person's worldview.

A worldview is a set of foundational beliefs about reality, being, nature, knowledge, and value. Normally, these beliefs are assumed, not defended. Your answers to some key foundational questions set the boundaries for what counts as evidence and what supports your beliefs.

- Cosmology: What is the most ultimate (or real) thing in the universe? Where are the origins of the universe? Who is God? Where did come from?

- Metaphysics: What is the essential nature of the external world? Is it ordered or chaotic? Is it material or spiritual? Why is there something instead of nothing?

- Anthropology: What is the essential nature of human beings? Who am I? Why am here? What will happen to me when I die?

- Epistemology: How is it possible for us to know anything at all? How do we justify our beliefs? What is truth?

- Ethics: What is my understanding of morality? What makes something good or bad, just or unjust? How should I live?

- Aesthetics: Are some things more fitting than others? How should we evaluate artistic expression? How do l evaluate beauty, style, and taste?

- History: What is my understanding of the meaning of history? Where am I going?

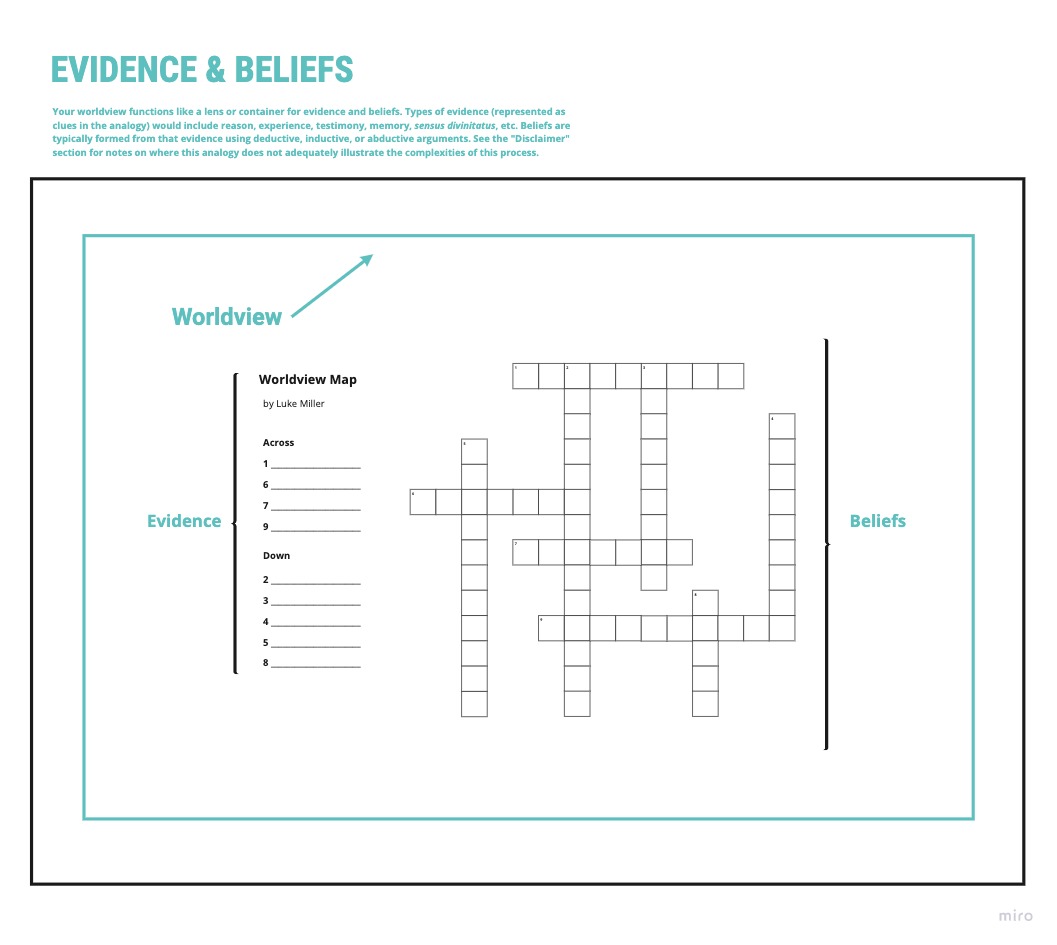

Your worldview is like a container for your evidence and beliefs. Possible evidence (or "clues") includes reason, experience, testimony, memory, etc. Beliefs (excluding basic beliefs) are typically inferred from evidence via argument (deduction, induction, or abduction).

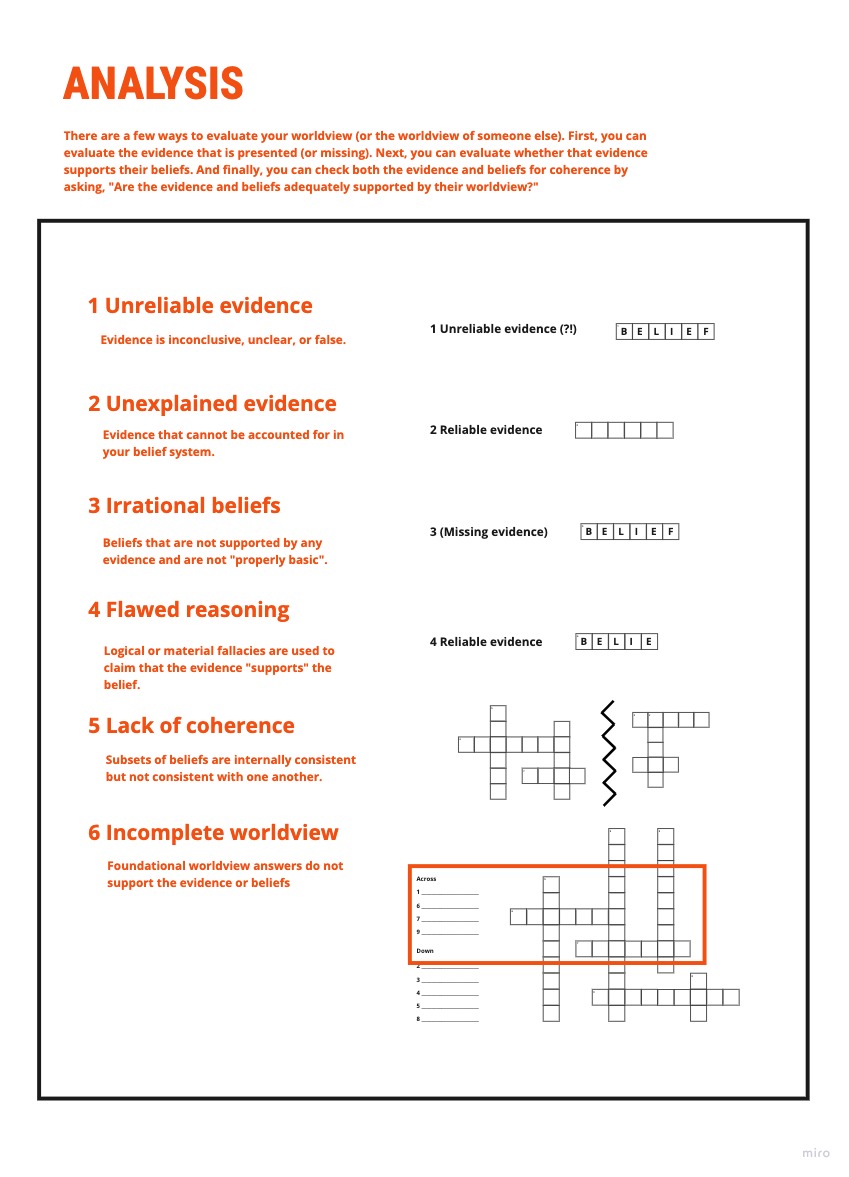

There are 3 main ways to evaluate a worldview:

- Test the evidence that is presented (or missing).

- Examine the evidence to see if it supports your beliefs.

- Check the evidence and beliefs for coherence (e.g. "Are they both supported by your worldview?")

DISCLAIMER: No analogy is perfect. This is especially true for one that attempts to represent the complexity of multiple fields of study (epistemology, philosophy, theology, and apologetics). So here are a few notes on the limits of this analogy.

1) Some beliefs are weighted differently based on how strong the evidence is for that belief. So it's possible for both evidence and beliefs to be more or less certain. For example, inductive and abductive arguments both involve probability, not certainty.

2) As noted in section 3, some beliefs do not have evidence, because they are "properly basic". They are not concluded from arguments, but inferred from experience. Non-circular evidence for these beliefs may not be available, so they are best evaluated by comparing them to the surrounding beliefs and addressing possible "defeaters".

3) Some evidence will be necessary to support multiple beliefs. In the analogy, this would be like one clue needing to have multiple answers that work for multiple answer boxes.

4) Conversely, some beliefs will be based on multiple pieces of evidence. Again, in the analogy, this would be like multiple clues needing to have the same answer SO they can work in multiple places.